Moving the climate crisis from our heads to our hearts

A summary of the key ideas and concepts I’ve gleaned from Britt Wray’s Generation Dread, interwoven with my own musings.

I took a psychology degree as an undergrad because I was fascinated by the brain. But a career in it felt too daunting, expensive and competitive at 21 and I turned instead towards communication and then eventually climate action. Britt Wray’s book and the growing recognition of the psychological impacts of the climate crisis feel like a circle back to my early love.

I’ve explored the value of emotional intelligence and shared the key learnings from Marc Brackett’s book Permission to Feel in an earlier big ideas book summary. What I love about Wray’s book is its direct application to our current times and her rationale that emotional intelligence will be crucial in order for us to navigate these times.

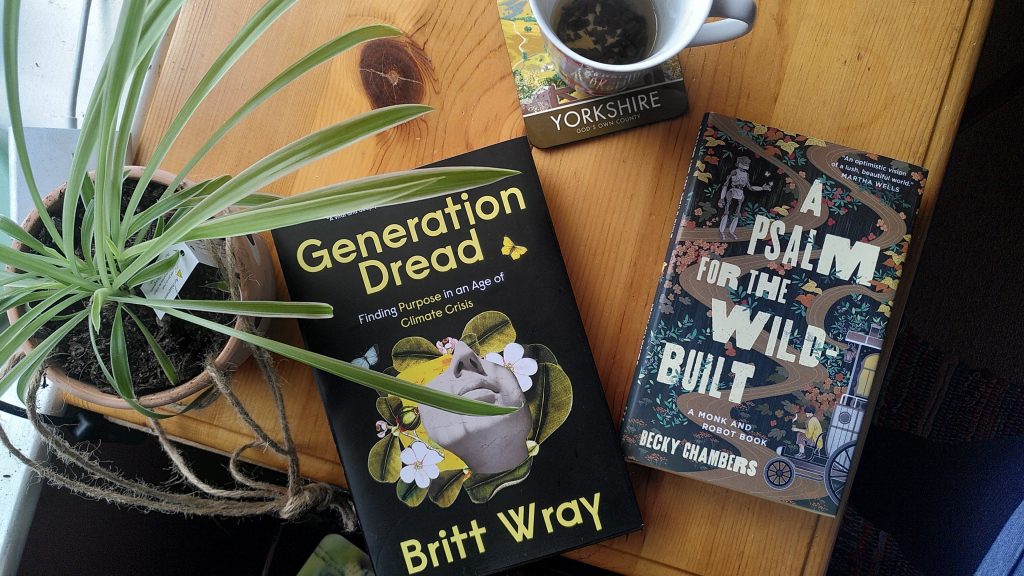

Generation Dread: Finding Purpose in a Climate Crisis reads like the perfect blend of story and psychological glossary and manual for this decade.

I feel the need to disclaim that what follows will not be fully objective. I have been a fan of Britt Wray since I stumbled upon her Twitter thread and TED talk back in 2019.

I responded to her question wondering if others were reckoning with reproductive anxiety in the Twittersphere. She replied back! Her openness about her journey of ambivalence around motherhood in a climate crisis has been a personal soothing backdrop to my own. Listening to her CBC radio show, she named some of the feelings I was having yet she dared to say them out loud. When I came up with the idea of storytelling around this topic, I dropped her a DM and she was curious to find out more. So we had a zoom call and she came on board the Motherhood in a Climate Crisis as a project champion. I was delighted.

When her book came out, I was excited and hesitant. I knew this book was needed, I knew I needed to read it, but I knew the material was going to be hard. Even when I decided to finally buy a copy, it sat on the bookshelf for a good few weeks. I have a romantic notion that the right book finds you at the right time. When I was working through some of my own grief, I reached for Britt’s words. I took a deep breath and began. To me, she wrote like a wild sister: she’s been there too and she reaches out a hand through the pages to act as a supportive guide. I had to take breaks, emotionally and intellectually, to let it all percolate and settle, but at its conclusion I knew this was a key text for me.

What follows is a summary of the key ideas that resonated with me in her book. In part, to help me process the concepts and in part a teaser for anyone curious to pick up a copy of the book too.

So let’s begin.

The book is divided into three sections, three signposts for “every soul who is overwhelmed by this crisis yet refuses to look away,” as she writes in her dedication:

- Feel it all

- Connect inward to transform oneself

- Connect outward to transform the world

1. Feel it all

Balancing privilege and validity

From the get-go, Wray acknowledges the tension and the wider critique of the climate movement: the idea that it’s a privilege to have the space for eco-anxiety and that existential threats have been around for many less privileged communities for centuries. And she balances that by acknowledging the very real distress it is bringing up for so many people.

Wray makes the connection between the climate crisis, racism and history so succinctly:

“Global warming is not only a natural result of burning fossil fuels, it is an extension and outcome of colonialisation as well.” Paraphrasing here, colonisation by Europe of other people’s land was in the pursuit of resources and extraction. “The Industrial Revolution evolved from these expanding conditions for European productivity, as did the bedrock of unequal social relations between white, Black and indigenous peoples.”

She pulls in words from Hop Hopkins, Sierra Club, “we will never survive the climate crisis without ending white supremacy… You can’t have climate change without sacrifice zones, and you can’t have sacrifice zones without disposable people, and you can’t have disposable people without racism.”

And the eco-grief is valid. Wray shares her own journey to dark places.

“It was in that moment that I realised that being struck every now and then by overwhelming eco-distress is not only a badge of compassion for the Earth and all life on it, it is to be expected. Mourning is the cost of attachment, so they say, and things are unravelling. Our grief is going to show.”

And what to do about it? Wray wrestles, “privileged anxiety about the climate, such as my own, must be harnessed and purposefully directed outward for justice-oriented results if it is going to be of help.”

What emotions can tell us

Far from the British cultural norms of hiding, ignoring or denying our emotions, Wray points out that “emotions are the gas you can’t smell or see, yet it fuels public engagement.”

When we don’t understand them, it has consequences: “our lack of wisdom about our own feelings and those of others is just as damaging when we talk about what is happening to the Earth and all the lives that are at risk.”

But when we do, it “may also be the only true resource we have”. Quoting the medical journal, The Lancet, “Recognising that emotions are often what leads people to act, it is possible that feelings of ecological anxiety and grief, although uncomfortable, are in fact the crucible through which humanity must pass to harness the energy and conviction that are needed for the lifesaving changes now required.”

However when it comes to climate change and the science in particular, it has been stripped of all its emotion, dehumanising scientists in the process. And to what end? Wray questions, “How are average people with relatively limited scientific knowledge supposed to confidently support the grave implications of this research when scientists can’t speak their full truth?”

Labelling the dark feelings – emotional terms for our times

Generally speaking, I find labelling a helpful tool, feeling a visceral relief when I finally have the words to explain a feeling or idea. So I was delighted to learn a range of new phrases from Wray or writers she references. Definitions in quotation marks are Wray’s, otherwise they’re acknowledged.

Ecological grief – “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecologic losses”

Environmental melancholia – Renne Lertzman: “describes the feeling of conflictedness that can occur when confronting environmental problems”

Anthropocene horror – Timothy Clark: “a sense of horror about the changing environment globally, usually as mediated by news reports and expert predictions, giving a sense of threats that need not be anchored to any particular place, but which are both everywhere and anywhere”

Global dread – Glenn Albrecht: ”the anticipation of an apocalyptic future state of the world that produces a mixture of terror and sadness in the sufferer for those who will exist in such a state”

Psychoterric emotions – Glenn Albrecht: “emotions related to perceived and felt states of the Earth”

Ontological insecurity – Anthony Giddens: a “person’s fundamental sense of safety in the world and includes a basic trust of other people”

Negation – a psychological defence: “our ability to fully push away what’s real.” Wray’s example is developers building homes in flood-risk zones

Disavowal – another psychological defence: “having one eye open and one eye closed at the same time”. Naming that common feeling, when we understand the gravity of the science and “simultaneously, we do not believe that things so terrible will ever come to pass.”

Learned helplessness – when attempts to achieve goals in the past fail, this means we approach the climate crisis with a degree of nihilism. But, Wray argues, because we’ve hardly tried to tackle the crisis, it’s “our narrative of powerlessness that is holding us back more than our actual capacities”

Climate anorexia – “where someone reduces their carbon footprint so much that they act as though it were best if they ceased to exist”

Solastalgia – Glennn Albrecht: “the homesickness you have when you are still at home…home is becoming more than unrecognisable: it is for many becoming increasingly hostile”

Disenfranchised grief – “grief that is not recognised” where there is often silence or taboo around it. This type of grief covers ecological grief but also around “suicide, abortion, pregnancy loss and infertility. Often, it is met with an invalidating response.”

pretraumatic stress – Lise Van Susteren: “before-the-fact version of classic PTSD” includes flash-forwards and hypervigilance

narrative foreclosure – Ernst Bohlmeijer: “the conviction that no new interpretations of one’s past nor new commitments and experiences in one’s future are possible that can substantially change one’s life-story”

Eco-distress and a framework

I love a good framework, it’s like a manual to understand hard things.

Understanding that eco-anxiety is an indirect mental health impact of climate change, as opposed to a more direct impact of depression – for example from losing your home from an extreme weather event – helped me place my emotions in a wider context.

Understanding a scale of eco-anxiety developed by Caroline Hickman from mild to severe with a corresponding list of symptoms helped Wray “make sense of [her] own experiences and feelings”

Wray is clear not to pathologise this. Arguing instead that “being maladjusted to a sick society can be a source of strength for taking on the life-protecting actions that are needed now.”

But to do that we need safe spaces and gentle “containment.” Why? Wray refers to Hickam here: to help move from “static guilt where we’re stewing in self-condemnation to animating guilt, the process of “bringing oneself to life around one’s guilt”.

I loved this idea from Wray: “Dread is a resource floating freely in the air, and it’s this generation’s job to capture it.” Because “when we have a change to process it, it can urge us to gather new information, reassess our life choices, find deeper purpose, and make important changes that can help bring about justice oriented societal shifts.”

Hell yes. It reminded me of Sharon Blackie’s Eco-Heroine’s journey into the underworld before she can return anew.

Some further resources

- Dr Gloria Wilcox’ feelings wheel – which I use in all my workshops

- Climate Psychology Alliance

- Sharon Blackie’s Eco-heroine’s journey – from her book, If Women Rose Rooted (affiliate link)

2. Connect inward to transform oneself

In the next section we shift gears, because this is not about navel gazing, this is about “the work.”

Wray gently critiques the knee-jerk reaction of those who have finally felt the climate crisis “in their souls” – the doing. So much doing. And she posits, “Why activism isn’t really the cure for eco-anxiety and eco-grief.” She criticises one of my favourite quotations of Joan Baez: “action is the antidote to despair.” I found this difficult to swallow until I read on.

Wray is exploring a concept that I’ve often wrestled with personally but had not zoomed out and connected it with this crisis. I’ll try and summarise; this current system, which is consuming itself, is founded on production and extraction, not only in our behaviours but it’s also deeply ingrained in our mindset as well.

Many forms of activism – actions out there demanding we take down this old world – are designed with our existing mindset of do more and feel less. And so what do we see in many forms of activism? High levels of burnout and cycles of despair. Wray captures it: “It’s a shortcut – a too-quick move from pain to action – and it threatens to leave people far less resilient and capable of facing the ecological crisis than they ought to be.”

We need to shift our minds and mindsets in tandem with our out in the world work. Wray refers to Caroline Hickman’s term of “internal activism”. I really like Elizabeth Lesser (author of Cassandra Speaks: When Women are Storytellers The Human Story Changes – affiliate link) phrase of “innervism”… “the part of me that seeks inner change, inner healing.”

Doing this work is transformative. Wray suggests, “It is the work that’s required to cope better with what’s overwhelming, and the work that can bring us to the far side of grief – where some strength and acceptance, and the courage to act, can be found.”

Turning towards the grief

Once we turn inwards, we need to turn towards the hard stuff. Wray invites us, “rather than refusing to acknowledge the pain that is part of being alive at this time, naming the losses that are unfolding in order to let grief rise to the surface can release energy for transformative change.”.. Grief can make us come alive again, and point us towards our life’s bigger purpose amidst climate breakdown.” Wray acknowledges that this is not easy work. Grief is often disregarded in our mainstream culture, so spaces to grieve need to be sought out.

Hope is a verb

I’ve loved the pulling apart of the concept of hope. In late capitalism it can feel passive, having hope that something or someone will save us (Have a read of my plea to Bonnie Tyler as she insists on Holding Out For A Hero). No – we need to “do hope”. Hence terms like Joanna Macy’s idea of “active hope”. Climate justice essayist Mary Annaise Heglar points out those of us seeing it as passive are coming from a place of privilege: “You’re supposed to have the courage first, then the action, and then you have the hope.”

Play in paradox

Wray’s pulling apart of the more nihilist communities, such as Deep Adaptation – and I would add near-term extinctionists – deeply moved me. I don’t think I’d inspected who was holding these narratives and she pointed out that it’s often older white men. She asks the reader, “how many different perspectives are you following? What mix of voices are you letting in?”

When the “doomer” voice creeps in, whether our own internal ones or others, she invites us to question the validity and ask what else might be true? She describes these stories as “emotionally sticky” but “such tunnel vision can have grave consequences for our wellbeing.”

How can we balance this? Wray suggests that without denying the size of the existential challenge, we can “still allow room for possibility and positive emergence.” And these times call for it. Why?

“What you people call collapse means living in the same conditions as the people who grow your coffee.” Wray is quoting Vinay Gupta here. Talk about a gut punch.

And so we must imagine possibilities like our lives depended on it. I hadn’t thought of it this way but this is why, through Rob Hopkins’ work in What Is to What If: Unleashing the Power of Imagination to Create the Future We Want (affiliate link) I was inspired to start Cli-Fi for Beginners. Every month we make a practice of being #OverDystopia and writing about climate solutions as though they were already so. And now I can see where this all fits.

Wray nips at my heels here, saying that, “Imaginings of the future are incomplete when one only sees what one wants to avoid.” This is important work because “self-care in a planetary crisis requires doing the work to keep your imaginative capacities alive.” She goes further and makers her own commitment to this practice, “a bright outlook must be nourished and that it is my duty to do whatever I require to keep my hope for the future alive.”

This notion of paradox is something Brene Brown talks about a lot. Brown says, “the mark of a wild heart, is living out the paradox of love in our lives. It’s the ability to be tough and tender, excited and scared, brave and afraid – all in the same moment.” It reminds me of that Carl Jung quote: “Only the paradox comes anywhere near to comprehending the fullness of life.”

Straddling this paradox is the work of our times. I’m trying to do this. It’s uncomfortable and real.

Emotional tools for our times

But Wray doesn’t leave us just with concepts, she litters this section with a range of tools we can equip ourselves with to navigate this work. Again, definitions in quotation marks are Wray’s, otherwise they’re acknowledged.

grounding – when you’re feeling overwhelmed “going to a sensory experience in your body and find what’s happening there.” Focus on a feeling, the clothes on your skin for example, or one sound, or on your breathing.

mindfulness – “an awareness of what’s happening in the mind”

forest bathing – “time spent intentionally in nature for therapeutic effect”

toggling – Leslie Davenport: “moving back and forth between distress over difficult information and states of resilience. Over time, we become familiar with the way in which we respond to that lateral motion, which is strengthening in itself”

reframing – Laura Schmidt: “when we can’t fix the predicament we are in, we have to reframe it in order to bear our discomfort and learn to strategise from there”

reinvesting into meaningful efforts – Good Grief 10 step programme: “reinvest the energy lost from experiencing anxiety and grief into life-affirming actions that are deeply meaningful”

emotional dwelling – Robery Stolorow; making spaces “to counteract unhelpful defences against apocalyptic anxiety..where you can both express your fear and darkest thoughts without anyone attempting to offer comfort, argue the validity of the feelings, or minimise their severity”

emotional reflexivity – “embodied awareness of how people respond to distress, engage with big problems and feel about the crisis”

deep determination – Jo Hamilton: “ongoing commitment to act for environmental and social justice” and “to live the future worth fighting for in the present”

protective survivor – Robert Jay Lifton: “someone who vividly imagines how they might perish and gets shaken to the core by the premonitions haunting survivor…She sometimes even finds joy in pushing against the seemingly inevitable, and would rather die trying, arm in arm with others, just like her, than in a state of surrender”

flexible thinking – “tolerating simultaneous opposing thoughts and even be empowered by them”

binocular vision – from having two eyes: “a perspective that allows us to maintain our state of awareness about the gravity of the situation, while having the capacity at our fingertips, through a gentle change of focus, to immerse ourselves in a radically different field of view”

deep ecology – a type of environmental philosophy that promotes the inherent allure of nature rather than its instrumental worth to humans

enchantment – Sharon Blackie: “a feeling of fully participating in the world, welcoming the mystery of things that cannot be explained, and embodying a sense of belonging and connection to things outside ourselves”

symbiocene – Glenn Albrecht: “the period of human history where we reintegrate with the rest of life”

Ecozoic – Thomas Berry: “a kind of Exodus out of a period when humans are devastating the planet to a period when humans will begin to live on Earth in a mutually enhancing manner”

decolonising therapy – “using alternatives to mainstream mental health models that can further emotional wellness on a larger collective scale for communities of colour

social capital – “potential of social relationships to allow residents in a community to coordinate their efforts and achieve shared goals”

The gift of uncertainty

Now that’s certainly a reframe isn’t it?! As someone who’s been conditioned to tightly control things to ensure certainty, seeing the gifts of uncertain outcomes takes some patience. But I’m beginning to see the light. Wray quotes Andrew Bryant’s eloquent invitation, “Not knowing can open up potentialities”. In complex systems many small actions can lead to tipping points. I’m familiar with the climate ones but Wray points out the social ones too. Wray pulls in Eric Beinhocker’s provocation, “The existential question is, which tipping point will we hit first?”

Here’s Wray’s call to action: “What’s going to happen next? Sit with that question. You’ll see that there is room for you to help shape the answer. It isn’t that a good outcome is likely, but various good outcomes within this mess are possible…we should trust uncertainty rather than fear it.”

Some further resources

- The Good Grief Network

- A related blog that explores our own mortality via the Death Cafe initiative and its links to climate change I wrote back in 2019

- Walks that reconnect

- Council of all beings

3. Connect outward to transform the world

In part three, with our “innervism” workout established we re-enter the wider world, “seeing with new eyes” as Joanna Macy would say.

At With Many Roots, we’re interested in the roots of words, or etymology. So you can guess my delight upon learning the Greek root for “apocalypse” means to reveal, lay bare, unveil or disclose!

And so, Wray suggests, “though it is too late to keep the world as it is today, it is far from over. It, in fact, is the beginning of something else.” She pulls on examples from history and civilisations: many peoples have made themselves anew many times.

Stand aside, become a partner and see with less binary

Putting humans on top and at the centre has led to a domination that is getting increasingly more dangerous in Western culture. So Wray encourages, “learning to decentre ourselves is part of a regenerative mindset that starts with the recognition of the substantial agency of all other species, and even of other natural features that science does not classify as living.”

Whereas other cultures have a more partnership-orientated model, functioning “as an interconnected web and values egalitarian, life-sustaining structures and mutually supportive systems.” It reminds me of Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics seven ways to think like a 21st century economist. Principle #5 is to be distributive by design. We’ve been thinking about this in how we run our business but here Wray invites us to go further.

It’s also in line with many indigenous cultures. But I appreciate Wray’s words of warning here: “the lives of Indigenous peoples everywhere have been mired in theft, dispossession and violence. Claiming indigenous knowledge as humanity’s saviour therefore carries its own risks of perpetuating harm.” The notion of gaining indigenous knowledge is laced with a dominating extractive mindset and needs to be unpicked. Her interview with Potawatomi scholar and activist Kyle Whyte had some really valuable insights for those seeking to be allies.

Wray does a phenomenal job in explaining the root of this severance in our monoculture of man and nature, in my opinion. As someone who has been conditioned in an empirical, rational us vs them mindset, throwing around the statement “we are nature” really grates on me. So when Wray explains the philosophical roots from Aristotle to Descartes today, I begin to get it. Dualism is an idea and now it’s time for a new one or an old-old one: “what the radical danger of this ecological moment calls on us to do is to muster whatever forces we can to close the chasm of separation.” She then throws a lifeline for us to get started.

Taking the grief public

This idea from Wray really struck me: “Grief is a private undertaking that can exist solely in one’s inner world, while mourning is the outward expression of grief.”

I’m writing this two days before the Queen’s funeral here in the UK. It might be the most British expression of mourning I have ever heard of: a 5 mile long queue that may take 18 hours to get to the front in order to pay respects to the Queen lying in State. For a culture that, in my opinion, doesn’t do “acceptable grieving” well let alone “disenfranchised grief” such as eco-grief, I am finding the mourning rituals jarring but endlessly fascinating (I find myself checking out the 24/7 BBC live stream of the queue a few times a day). The way I can begin to understand it is to tap into the Irish-side of my heritage and recall that when someone dies there, everything stops, and many many people pay their respects to the family and the person who has died, often with an open casket. You would attend a funeral for a much wider circle of people than the culture I’ve experienced in the UK.

Wray invites us to reflect that public mourning can also be used to “stand in power against injustice”, Think of the recent displays following police violence in the US and in the UK. I felt the power of the XR red rebels at all the rebellions: there was something theatrical and poignant in their silent movements.

Art, elaborate funerals, eulogies, etc are all examples of public mourning that can be powerful acts because Wray writes, “Mourning is more than a movement through grief – it is a way to mobilise.” These are often rituals and I love the call for a “ritual renaissance for the Anthropocene”. In our ritual-illiterate dominant culture here in the UK, the ones that remain are so commodified I’ve rebelled against them. But this idea is one I want to get on board with.

Shifting towards a culture of care in community

A concept Wray points towards is also something I have been learning from Jo McAndrews in the Motherhood in a Climate Crisis: we need to decolonise therapy from the couch and back into the community.

As someone who took a long time to build up the courage to see a therapist, this is a big reframe for me too. But here’s Wray’s perspective that hit me sideways, “the standard for therapy that’s widely in use today, which happens one-on-one and at high cost, was built from a colonial and individualist biomedical perspective.”

And in a recent article from clinical psychologist, Sanah Ahsan, highlights how our current model does not extend to look at how our current system is contributing to our distress. Ahsan states, “they encourage us to adapt to systems, thereby protecting the status quo.”

“If a plant were wilting we wouldn’t diagnose it with “wilting-plant-syndrome” – we would change its conditions. Yet when humans are suffering under unlivable conditions, we’re told something is wrong with us, and expected to keep pushing through. To keep working and producing, without acknowledging our hurt.”

I’ve been a member of Climate Psychology Alliance for a few years now, and their model of climate cafes is an example Wray suggests that is dismantling the traditional model. Mental Health First Aid is another model, as well as training up community members in these skills to build up community connectedness and resilience.

Wray concludes, “The sooner we realise that no one is coming to save us, and that we must do it together ourselves, the better off we will all be.”

Some further resources

- Global Environments Network Grief Toolkit: embodiment tools and rituals to support grief work in the community

- Climate Cafes

- Grief tending in the community

- Project Inside Out

- Climate Psychology Alliance

- Mental Health First Aid

Final reflections

This is a book for our times. And it found me just when I needed it. Wray put words around what I was feeling and gave me a new language to equip me in my personal and professional life.

Emotions, not just knowledge, are key to driving action. And the inside work is just as important as the outside work.

Although I’ve plucked out some of the big concepts, Wray also weaves in her personal story throughout this book, particularly her exploration of parenthood. This is a topic I’ll pick up in a separate post. I find her words relatable, stretching and affirming.

I’ve already been recommending this book to anyone who’ll speak to me, and particularly to those working in the big systems change space. There are no quick fixes, so how we build up our resilience is crucial in how we show up to our work.

Want to get your hands on the book?

I love the aims of Bookshop.org and their “design to distribute” model of their affiliate scheme. I earn 10% of each sale I generate through this link.